By Sunidhi Ramesh

|

| Racial and ethnic discrimination have taken various forms in the United States since its formation as a nation. The sign in the image reads: "Deport all Iranians. Get the hell out of my country." Image courtesy of Wikipedia. |

From 245 years of slavery to indirect racism in police sanctioning and force, minority belittlement has remained rampant in American society (1). There is no doubt that this history has left minorities in the United States with a differential understanding of what it means to be American and, more importantly, what it means to be an individual in a larger humankind.

Generally, our day-to-day experiences shape the values, beliefs, and attitudes that allow us to navigate the real world (2). And so, with regards to minorities, consistent exposure to these subjective experiences (of belittlement and discrimination, for example) can begin to shape subjective perceptions that, in turn, can mold larger perspectives and viewpoints.

Last spring, I conducted a project for a class to address the reception (3) of white and non-white, or persons of color (POC), students to part of an episode from American Horror Story: Freak Show. The video I asked them to watch portrays a mentally incapacitated woman, Pepper, who is wrongfully framed for the murder of her sister’s child. The character’s blatant scapegoating is shocking not only for the lack of humanity it portrays but also for the reality of being a human being in society while not being viewed as human.

Although the episode remains to be somewhat of an exaggeration, the opinions of the interview respondents in my project ultimately suggested that there exists a racial basis of perceiving the mental disabilities of Pepper—a racial basis that may indeed be deeply rooted in the racial history of the United States.

The premise behind my project was the understanding that past experience informs

In 2010, for example, researchers at the University of Pittsburgh found that internalized stigma among African Americans had a direct relationship with attitudes towards their mental heath treatment (4); in general, African Americans in this study reported more negative attitudes toward mental health treatment, and, as compared to their white counterparts, African Americans were less likely to seek out mental health treatment and were more likely to hold negative views about themselves if they were diagnosed with a mental illness (4).

Another study conducted in 2012 validates these results, finding that African Americans are significantly less likely than other race-ethnic groups to have received mental health services (5); although the article begins to tie this trend to education differences among the different racial groups, a definitive explanation for the relationship between race-ethnicity and the receipt of mental health services could not be found (5).

Beyond studies regarding the specific treatment of mental illness is research that questions the root of mental illnesses such as depression; one such study found a “clear, direct” relationship between perceived discrimination (which arises from “formative social experiences”) and symptoms of depression in Mexican-origin adults in California (6).

The conclusions drawn in these studies as well as those in other similar research imply that mental illness does not stand on its own; it, in fact, is a factor that is intertwined (rather strongly) with race as well as elements that underlie race such as discrimination and education.

Because the subjective experiences faced by minorities formulate differential understandings and subjective perspectives, these perspectives (according to these studies) can then go on to create different attitudes towards mental health. Ultimately, this cascade can form bigger more personal feelings such as internalized and public stigma.

With this comes a question: what if the differences in the way POC and White Americans are treated (either for mental illnesses or in general) manifest themselves in how different racial groups perceive mental health?

|

| A photo of a freak show exhibition, taken around 1941. The sign at the top reads: "Human Freaks Alive." Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons. |

Before getting into my project, I must mention that Pepper, throughout American Horror Story, is part of a “freak show”—a term that the dictionary defines as “a display of people with unusual or grotesque physical features as at a circus or a carnival show."As I was watching the show for the first time a few years ago, I was appalled at how it presented the reactions of people who interacted with the “freaks.” There was shock, amusement, fear, and even a sense of superiority. In one scene, the circus actors went out to a diner and were immediately kicked out on the grounds of “disturbing and scaring the other customers.” More often than not, the families who attended the circus would disrespect and taunt the performers.

I later realized that this scene illuminated the major difference between physical disability and mental illness. Physical disability can be seen; it is outward and apparent to a point where it can be identified and acknowledged as easily as it can be mocked and ridiculed.

Mental illness cannot. It is invisible, an uninvited guest that only the patient can feel, describe, and identify. It is silent. Quiet. Unseen. (This distinction regarding mental illness is why hundreds of articles with titles such as “I Don’t Believe in Mental Illness” and “9 Signs Why Your Mental Illness is Made Up for Attention” plague the Internet.)

People who bear mental illnesses are told that their symptoms are not real, that “laziness explains 100% of mental disorders,” or simply that their illnesses “does not exist.” These kinds of perceptions build up and begin to create stigma around mental illness.

Statistically, three out of four people who experience mental illness today have reported experiencing stigma. This stigma leads to feelings of shame, hopelessness, distress and misrepresentation in media. It discourages patients from seeking necessary help. It frames mental illness as a shameful blemish and weakness.

And in many cases, stigma and discrimination come hand in hand; often, those with mental illnesses and disabilities are denied employment, housing, insurance coverage and general social interactions such as friendship and marriage (7).

Worst of all, this very stigma throws mental health patients into a dangerous cycle of social isolation and harm.

According to a 2002 research paper written by Allison J. Gray, “Discrimination alters how patients see themselves, their self worth and their future place in the world. The immediate psychological effects of a psychiatric diagnosis include disbelief, shame, terror, grief, and anger” (8). She then argues that these patients eventually face social isolation, which directly leads to high rates of self-harm and suicide.

So, how and where do we go from here? Can we work toward destigmatizing mental illness?

Or is this a lost cause? Could the racial discrepancy between perceiving disabilities be too deeply rooted to change how these conditions are perceived? And where does this racial difference come from?

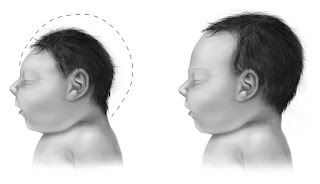

For this small preliminary class project, I asked ten respondents (five white and five POC) to watch the aforementioned 30-minute clip. This episode covers the experiences of a young woman, Pepper, who suffers from microcephaly, a rare neurological condition “in which the brain does not develop properly, resulting in a smaller than normal head” as well as intellectual disability, poor speech abilities, and abnormal facial features. In the clip, Pepper is introduced into the care of her older sister and her brother-in-law, a couple that later gives birth to a deformed child. Although Pepper cares for and loves the child as her own, her caretakers appear to be overtaken by “the burden” of having to deal with two individuals who are unable to fully look after themselves. In response, Pepper’s brother-in-law (with permission from his wife) murders the infant and places the blame on Pepper, who is unable to speak for herself but seemingly unaware of the injustice done to her. At the end of the clip, Pepper is placed in an insane asylum, forced to live there due to her supposed involvement in the brutal murder of her sister’s child.

|

| A comparison between head sizes for a child with microcephaly and a normal child. This change in head shape is often attributed to abnormal brain development. Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons. |

Following the viewing, I asked each respondent seven questions regarding their overall feelings as well as what characters and parts of the plotline resonated with them the most. In the end, I found three general categories of responses—each of which was clearly divided racially.

The most striking of these categories was, by far, how the white and POC respondents referred to Pepper’s microcephaly. I should preface with the fact that the episode never directly labeled her condition, and Pepper’s mental and physical statuses were not referred to as a disability in the scenes the respondents viewed. Still, every white interviewee spoke of Pepper’s condition as a “disability”—a handicap that allowed her to be bullied by her family and the justice system. These students seemed to dwell on the idea that Pepper was subordinated in the minds of those around her. To them, she was bullied for and handicapped by her mental state.

The POC respondents, on the other hand, did not use the words “disability” or “handicap.” Instead, they speak of her as an “outsider,” a deviation from what it means to be “normal.” This word, “normal,” was raised by every POC respondent. These students chose to discuss Pepper’s experiences in light of their own by drawing parallels between what it means to be a functioning, “normal” member of this society and the consequences of being the opposite, when an individual deviates from those norms (discrimination and outcasting).

Although these data are just preliminary, the implications, if these results held true with a larger pool or participants, are tremendous. At the least, these outcomes suggest that human perceptions of mentally and physically compromised individuals are racially based— that there may exist a socially constructed phenomenon for why white respondents viewed Pepper as “disabled” and POC respondents saw her as simply “not normal.”

If anything, the tendency for the POC individuals in my interviews to focus more on the aspects of being “normal” (rather than being discriminated) suggests something about the more personal aspects of the minority experience. It is possible that this theme was so salient because the question asked for the interviewees to relate the clip to their own personal lives (9); perhaps the notion of mental disabilities is not as prominent to these POC individuals as it may have been to the white respondents (as was suggested by the public health studies on POC Americans and mental health). Again, the validity of this statement should be explored through further research.

|

| Schlitzie (born Schlitze Surtees) was an American sideshow performer; Pepper's appearance and story are said to be based on Schlitzie's life. Image courtesy of Wikipedia. |

Whatever the case, the answers to these questions are not clear. They may never be clear or easy to address—unless we are somehow able to pinpoint exactly where these entangled differential perceptions stem from or whether or not they can be changed. What can change, however, is the stigma around mental illness.

If the relationship between subjective experience, differential understanding, subjective perception, different mental health treatment and attitudes, and stigma exists, can we tap into breaking the cycle? Can we try to change mental health treatment by better educating our doctors and mental health professionals? Can we change mental health attitudes by better explaining conditions to patients or the general public? Would changes in the initial subjective experience (reducing discrimination, for example) reduce mental health stigma down the line?

And would this stigma be alleviated with more evidence for a biological basis to mental illness? Possibly (10, 11, 12).

But this would require research as well—research that is deliberately designed to avoid reinforcing negative stereotypes. In other words, while bias is inherent to some degree in all research, specific biases such as gender and racial bias need to be consciously monitored in this research to avoid being implicitly implemented into the research process.

How can this be done? The Journal of European Psychology suggests engaging in introspection to acknowledge any biases before the research is conducted, including different types of people and viewpoints on the research team, standardizing procedures for data collection and checking for statistical significance—all while being aware of the errors and omissions that may be embedded in the research itself. Maybe, with these cautions in mind, we can work towards more direct, objective research that can lead to the lessening of stigma (especially towards specific races) around mental illness.

Until then, we must begin to realize that perception of mental illness is not black and white; it is socially directed, differentially interpreted, and variably understood. More importantly, it is profoundly engrained in experience and identity.

This understanding needs to come first.

Perhaps then we can begin to unravel the answers to the bigger questions we have.

Note: The students in my project were asked to watch two segments from Episode 10 of Season 4 of American Horror Story: 1) 31:53 to 37:20 and 2) 38:41 to 49:00.

References

1) Piazza, James A. "Types of minority discrimination and terrorism." Conflict Management and Peace Science 29.5 (2012): 521-546.

2) Rokeach, Milton. The nature of human values. Vol. 438. New York: Free press, 1973.

3) Shively, JoEllen. "Cowboys and Indians: Perceptions of western films among American Indians and Anglos." American Sociological Review (1992): 725-734.

4) Brown, Charlotte, et al. "Depression stigma, race, and treatment seeking behavior and attitudes." Journal of community psychology 38.3 (2010): 350-368.

5) Broman, Clifford L. "Race differences in the receipt of mental health services among young adults." Psychological Services 9.1 (2012): 38.

6) Finch, B. K., Kolody, B., & Vega, W. A. (2000). Perceived discrimination and depression among Mexican-origin adults in California. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 295-313.

7) Office of the Surgeon General (US, & Center for Mental Health Services (US. (2001). Culture counts: The influence of culture and society on mental health.

8) Gray, A. J. (2002). Stigma in psychiatry. Journal of the royal society of medicine, 95(2), 72-76.

9) Trepte, S. (2006). Social Identity Theory. In J. Bryant & P. Vorderer (Eds.), Psychology of Entertainment (pp. 255-271). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

10) Corrigan PW, Watson AC. At issue: Stop the stigma: call mental illness a brain disease. Schizophrenia bulletin. 2004;30(3):477-479.

11) Corrigan PW. Lessons learned from unintended consequences about erasing the stigma of mental illness. World psychiatry : official journal of the World Psychiatric Association. 2016;15(1):67-73.

12) Insel TR, Wang PS. Rethinking mental illness. Jama. 2010;303(19):1970-1971.

Want to cite this post?

Ramesh, Sunidhi. (2016). "American Horror Story" in Real Life: Understanding Racialized Views of Mental Illness and Stigma. The Neuroethics Blog. Retrieved on , from http://www.theneuroethicsblog.com/2016/11/american-horror-story-in-real-life_22.html